Intro to Python with Turtle Graphics

How to Draw Graphics with the Default Python Installation

The introduction to programming that makes the most sense to me would be to use the turtle module in Python. I was not lucky enough to be introduced to the turtle as soon as I was introduced to Python, it would have been so much more pleasant if we had been acquainted at first.

The idea of the turtle is that it is a cursor that you can see, and by giving it instructions you can draw pictures with it. Turtle graphics were developed by Seymour Papert in the late 60's as an instructional aid for children to use to become familiar with computers. The turtle is so called because originally it was a robot with a dome that resembled a turtle. Under the dome were wheels. It was tethered by a ribbon cable to the computer that sent it instructions.

The vision was to get kids to learn to draw pictures based on the mathematical principles of geometry so that they could use the computer to model the world of their experience. What the turtle basically did was make relative movements. It would not go to a location, but move forward or backward so many turns of the wheel from where it was. It would turn right or left by so many degrees, and it carried a pen that could leave a trace of its progress on sheets of paper from huge rolls. Papert thought this would give the children a chance to understand this relative movement in relation to their own bodily movement in space. He called it body-syntonic reasoning.

I note that Stanford's CS106A course, intro to programming for computer science, also began with a demonstration based on a representation of a robot. This was called Karel, which had with a similar set of basic functions as the turtle. Karel could move, sense, encounter objects and color the square it was on.

Let's use Python's turtle module.

There are a lot of different program editors out there. When I started with Python I was following the old version of "Learn Python the Hard Way" and the author's suggestion was writing programs in a basic text editor, like notepad. Just like the way I started using HTML in the 90’s. I have a new intro to Python now for Version 3, called "Think Like a Computer Scientist, Programming with Python 3" (or try the online version).Which advises the use of an editor called PyScripter. That editor does have some cool features. Honestly, most of the time I prefer just using IDLE, the editor that comes with Python. It is certainly faster than starting each script at the command prompt as Zed Shaw suggests.

Since Python is an interpreted language as opposed to compiled, like C or Java, it is common to refer to a python program file as a script. It's in human-readable programming language in a standard UTF-8 text file with a .py extension instead of text. If you have Python installed on your computer then you can type the path and filename in the command prompt as an argument to python, and it will run the program, whether at a command prompt or by opening a window, like with their window-making toolkit tkinter, which the Turtle module uses.

C:\\users\GreenWizard\python\python triangle.py

Anyway, to use turtle you would type something like the following in a text file you've renamed into a .py file:

import turtle

screen = turtle.Screen()

t = turtle.Turtle()

unit = 200

for i in range(3):

t.left(120)

t.forward(unit)

turtle.done()

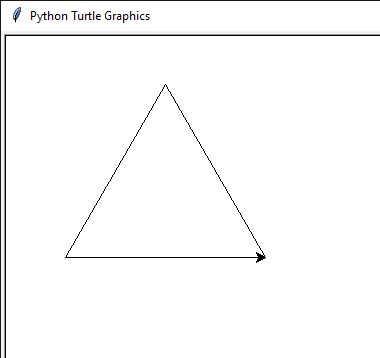

If you run the script it should open a window in which a little pointer draws a triangle by leaving a line behind it as it moves.

Let’s look at what each line of the program does:

import turtle < here we imported a module, it is another python file with tools for drawing lines and things on screen.

screen = turtle.Screen() < here we use the name screen to hold the instance of the capital s Screen() object, to which we might pass commands, for instance to change the background color.

Programming languages are highly specific and sensitive to capitalization and punctuation marks. Python is also sensitive to indentation. For the program to function properly, it must be typed exactly. You must use capitals and lowercase letters where required. You must use exact punctuation marks, spacing and indentation. Once you have assigned the capital s Screen() object to the variable screen, you have to type screen in lowercase, or it will not be recognized as the name you gave the Screen() object.

I also frequently have issues with Python syntax errors with line indentation. The style guide to python suggests using 4 spaces for indentation, for instance the for loop in this version, or the function definition in the later example. The indentation is what lets Python know that those lines are part of that section, that they are encapsulated within the loop and are one of the commands to be repeated or else are one of the commands in the function to be run with the other commands when the function is called. Many editors made for writing programs with python can be configured to interpret the tab key as inserting 4 spaces, you could do it manually, or if you use a default tab, as long as it is consistent within the file, it should work in most cases.

t = turtle.Turtle() < here we assign a variable name to quickly refer to that cursor that we use to draw lines on the screen.

unit is a variable that I use here for convenience and standardization. It is convenient to be able to change the default unit at the start thus setting the scale.

I then declare a for loop, initialized with single-letter variable i, the range() object gives a natural count, though of course that begins with i = 0. Note the use of the colon, indicating that what follows is the loop. Within the loop I only call two basic functions: t.leftturn(120) the reflex angle or external angle in degrees of 60

then I move forward one unit, and repeat.

I close the program with: turtle.done() note I did not use my abbreviation. This function is addressed to the module not the Turtle object. As a way of closing this seems as good as turtle.mainloop() which would seem to imply waiting for user interaction rather than draw a scripted shape. When you run it in many environments, (at command prompt, powershell, pydroid), the window will tend to close right after the last instruction unless you use one of these.

One part of programming is calling specific names in your script in the right way to get the functions that will do what you want. Another part of it is using the basic functions, applied mathematics and logic, to develop your own procedures. In this intro program we are using a bit of both. Let me highlight a few things starting from the beginning.

The first line, our import statement. Other programming languages offer similar capabilities. In Java, we can call for libraries of pre-defined functions, such a statement in Java might look like:

DrawFractal extends GraphicsProgram

Which likewise calls to a superclass, a library of defined functions and containers for your specific data. in CS106-A we called on the graphics program to take our instructions to draw circle at 200 on x and 200 on y, here we have called the turtle draw lines in a similar way.

screen and t are our variable names. We could have called them anything. By assigning these objects to a variable we have created instances of them. If we wanted to, we could have created multiple instances. We could have a script that runs two turtles on a screen, perhaps named alice and bob (Python's style guides recommend using lowercase variable names)

In this example I used a for loop, which is an easy, self-contained way of repeating a set of instructions. The variable i here is one of the only places that the Python style guide countenances a single-letter variable. it is a throwaway variable that exists only in the scope of the loop. Once the loop is terminated, you probably won't call on it again, and if you write a new for loop with the same variable name, it will be reset.

Let's change up the program a little:

import turtle

screen = turtle.Screen()

t = turtle.Turtle()

screen.bgcolor("black")

t.pencolor("white")

t.pensize(2)

unit = 200

colors = ["red", "yellow", "blue", "light green", "hot pink"]

def draw_triangle(size, color):

t.color(color)

for i in range(3):

t.left(120)

t.forward(unit)

for i in range(9):

draw_triangle(unit, colors[i % 5])

unit *= 0.8

t.penup()

t.right(15.3)

t.forward(0.15 * unit)

t.pendown()

turtle.done()

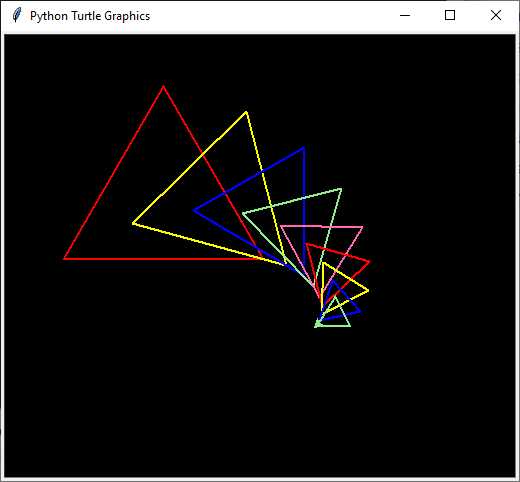

There is a bit more going on here, but not so much that we'll get lost, I think. I've added a bit more to the setup. I've changed the colors to take the program away from the black & white default and add some neon lights at night kind of pizzaz. I made the pen size a little larger for the same reason. An expanse of black tends to swallow fine lines. I gave a default color, which I really only used when testing this. Notice that some of the parentheses that were empty now have values in them, some of the first of these are strings. Strings are a series of letters enclosed with quotes. Knowing the libraries, modules or functions that you are going to use includes knowing which functions take which kinds of parameters. Some programming environments, (IDLE, Pyscripter) will tell you which kinds of data each function takes as an argument.

I added a list, assigned to the variable name colors. A list is a built-in data type in Python. It is one of the most versatile such types. It is more or less equivalent to an array as described in other programming languages. The list is defined by the square brackets. Different items in the list are separated with a comma. The items in this list are all strings. They are marked as strings by being enclosed in quotes. Python allows strings to be defined either by double quotes or single quotes. My prior experience leads me to prefer double quotes. These are colors that the turtle module recognizes as pre-defined valid arguments for the color setting. Colors can be specified in other ways too, like with a hexadecimal triplet, which must also be passed as a string.

"def" is a Python keyword that defines a function. I defined a draw_triangle() function to encapsulate the loop I wrote before for drawing the triangle. I also added an argument for the color. The function takes two arguments, size and color, which from their inclusion in the parentheses to the end of the indented block are separate from their use in the rest of the program.

I then made a new for loop, using the same single letter variable, to demonstrate the limits of this variable's scope. The first command in this loop is a call to the function to draw a triangle. Defining a function and calling a function are different. Functions defined still don't do anything until they are called. When they are called they must be given the right type of arguments or parameters. In this case I am passing unit, as defined at the head of the program, and which will take the place of size within the function definition.

I am also calling on the colors list with an expression within the subscript notation. In this case the square brackets attached to colors holds a mathematic statement that gives the criteria for which list item will be chosen. the statement is i % 5, which means I am using the index variable of the current count of the loop and taking the remainder when it is divided by 5, the length of my list. This means that each time the loop runs a different color from the list will be chosen in order, repeating as the end of the list is reached. The percent sign is called modulo in Python, and returns the remainder of division. It makes the list into a wheel, or a ring instead of a line.

unit *= 0.8 means I am diminishing the size of the triangle with every iteration. This is Python shorthand for multiply the variable by the factor and update the content of the variable to the new value.

t.penup() allows me to move the turtle without drawing a line.

I rotated the turtle, and have a math expression instead of a single number for the argument to move the turtle forward. This distance will change as the value in the unit variable changes within the loop, but it will change proportionally with the size of the triangles being drawn.

t.pendown() after I move the turtle, I want to be prepared to draw the next shape.

You should feel free to make changes to the program and get it to do other things. Try gradually increasing the number of iterations in the loop. Experiment with different factors for diminishing the unit, or moving or rotating the turtle between triangles. Try putting the commands inside each loop or function in a different order, and see what happens. See if you can define functions for drawing other shapes. More turtle commands can be found here: https://docs.python.org/3/library/turtle.html

The promise of getting the same results with less typing is part of what made me switch from Java to Python in the first place. Maybe you’ll appreciate that. You can write forward as fd(), left as lt(), right as rt().

Another thing you can try is actually open the turtle and pass it commands one at a time, through the interpreter instead of running a script. My main way of doing this is with IDLE, but it also works running the interpreter in a command window or the powershell.

For many years I've been interested in geometric constructions, such as the Golden Rectangle and the steps involved in constructing the Golden Spiral, pentagram, heptagram and other star shapes. The drawing tools I learned in my younger years, Photoshop, Illustrator, etc. were insufficient because they were not mathematically precise. I then began using Geogebra. Using the turtle for the same constructions is a very different experience. For one thing, to make the construction in Geogebra, like with a compass and ruler, you don't need to know any numbers or ratios. You don't need to measure the angles to follow the procedure of making an equilateral triangle, or square, or pentagon. When using the turtle though, you do. You have to know or calculate the lengths, and angles. The way Geogebra gets around having you explicitly state such numbers is by detecting the intersections of lines. I’ll show you how I do this with the turtle later. We can work with coordinates and functions related to real geometric formulas.

Whether you are interested in geometry or not, the turtle gives a kind of detailed visual feedback of what a program is doing. You can use it to see the effects of various data types and program structures. Let math be visible.

Happy Equinox!

I added Amazon affiliate links where appropriate.